Fifteen Crosses

- smegburke

- Apr 18, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: May 14, 2025

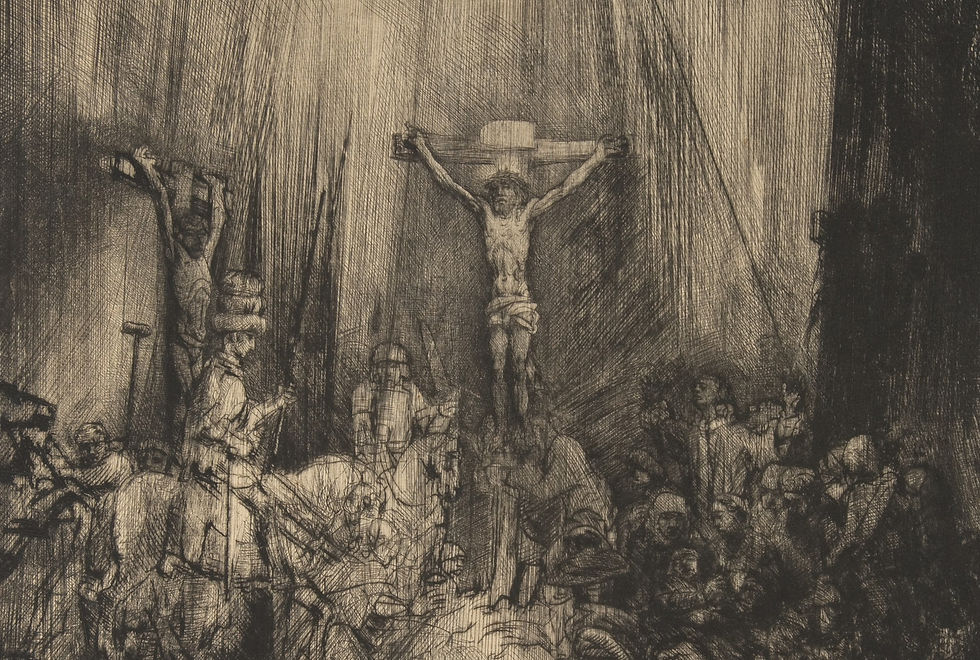

Good Friday seems a fitting time to revisit Rembrandt’s "The Three Crosses," which I discovered during a course on Rembrandt and Henri Nouwen. For me, Nouwen's writings and Rembrandt's artwork in its five reworked states offer glimpses of relationship with Christ through suffering, seeking to become available and present even in life's hard places.

Both Nouwen and Rembrandt were well acquainted with suffering. The years Rembrandt made these works were a time of considerable difficulty, when he began auctioning off his possessions and declared bankruptcy. His Bible was one of the few items he kept with him to the end of his life.

The Three Crosses, Versions 1-3

The first three versions of "The Three Crosses" emphasize the crowds teeming about the cross. Some are desolate, some indifferent. Those who do not seem attentive, or are present in mockery set the grieving followers in vivid contrast. The earlier states emphasize the centurion’s revelation kneeling at the foot of the cross. We seem to see his declaration “Truly this was the Son of God,” (Matt 27.54, KJV) He is one of the few figures who gaze squarely at Christ, truly seeing Him for the first time.

There are other figures who are sorrowfully affected by Christ’s death. A cluster of mourners surrounds Mary, Jesus’ mother. A figure thought to be John, the only disciple that Jesus addresses during the crucifixion, stands out against a patch of darkness. The figure at the foot of the cross may be Mary of Bethany, who John’s gospel describes as anointing Jesus feet with her hair, once more with her head at Christ’s feet. Perhaps it is Mary Magdalene who is explicitly mentioned to be present near the cross (Jn. 19.25).

The Three Crosses, Versions 4-5

The later states have a visceral darkness cast over the scene. Dramatic chiaroscuro shrouds the impenitent thief, and renders the group of women within this blackened atmosphere. A soft, yet turbulently etched light focuses on Christ and the penitent thief. John now stands with outstretched and imploring arms, in a gesture much like the crucified Christ. The centurion has almost disappeared.

Here we see one of Rembrandt’s last explorations of the crucifixion, capturing the widest scope of all his artworks on the Passion. As he works towards the final states of "The Three Crosses," subduing the presence of peripheral figures, it may be that he is seeking to create a scene intimately focused on Christ.

My time spent with "The Three Crosses" and Nouwen's writing has challenged me to consider making my experiences and suffering available to others. In "The Wounded Healer" Nouwen wrote "Jesus has given the story a new fullness by making his own broken body the way to health, to liberation and new life. Thus, like Jesus, those who proclaim liberation are called […] to make their wounds into a major source of healing power."

He brings to mind Paul’s dual aspiration: “I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the sharing of his sufferings by becoming like him in his death” (Phil. 3.10). I am still learning to live faithfully and openly in this area.

I expect this may take time. Nouwen looked back on his lifelong journey and remarked "I stand in awe at the place where Rembrandt brought me. He led me […] from the place of being blessed to the place of blessing. As I look at my own aging hands, I know that they have been given to me to stretch out toward all who suffer, to rest upon the shoulders of all who come, and to offer the blessing that emerges from the immensity of God’s love."

In "The Three Crosses" we see the immensity of God’s love, enfleshed and given in Christ. I see an invitation to regard my suffering in light of Jesus’ ultimate suffering, and to be poured out to others with Him. It seems that Rembrandt has made available his contemplations and identification with Jesus, his suffering and crucified Saviour. This is both a challenge and encouragement to me, as I seek opportunities and the courage to do the same.

Image Credits: The Three Crosses, Rembrandt, 1st state, British Museum The Three Crosses, Rembrandt, 2nd State, Metropolitan Museum The Three Crosses, Rembrandt, 3rd State, British Museum The Three Crosses, Rembrandt, 4th State, Metropolitan Museum The Three Crosses, Rembrandt, 5th State, printed posthumously by Frans Carelse, British Museum

Sources:

Peter Black with Erma Hermens, “Rembrandt’s Passion Subjects,” in Rembrandt and the Passion. Munich: Prestel, 2012.

John I. Durham, The Biblical Rembrandt: Human Painter in a Landscape of Faith. Macon, Ga: Mercer University Press, 2004.

Nouwen, Henri J. M. The Wounded Healer: Ministry in Contemporary Society. Garden City, N.Y.: Image Books, 1979.

Charles M. Rosenberg, Rembrandt's Religious Prints: The Feddersen Collection at the Snite Museum of Art. 2017.

Joachim von Sandart and Filippo Baldinucci, and Arnold Houbraken. “Lives of Rembrandt” Translated by Charles Ford and Ulrike Kern. Los Angeles, Getty Publications, 2018.

Nicola Suthor, “Views on Dutch Painting of the Golden Age, Rembrandt’s ‘Three Crosses’”. Yale University Art Gallery, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X4Vaw7bqbpU

Ilja M. Veldman, “Protestantiam and the Arts: Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Netherlands,” in Seeing Beyond the Word: Visual Arts and the Calvinist Tradition. Edited by Paul Corby Finney. Grand Rapids, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans Pub, 1998.

Comments